A Critical Commentary on the “Global Horizon Scan of Emerging Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Hydropower”

A recently published preprint, “Global Horizon Scan of Emerging Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Hydropower,” authored by Irene Boavida and 36 coauthors, offers a compelling look into the industry’s view of its own future.

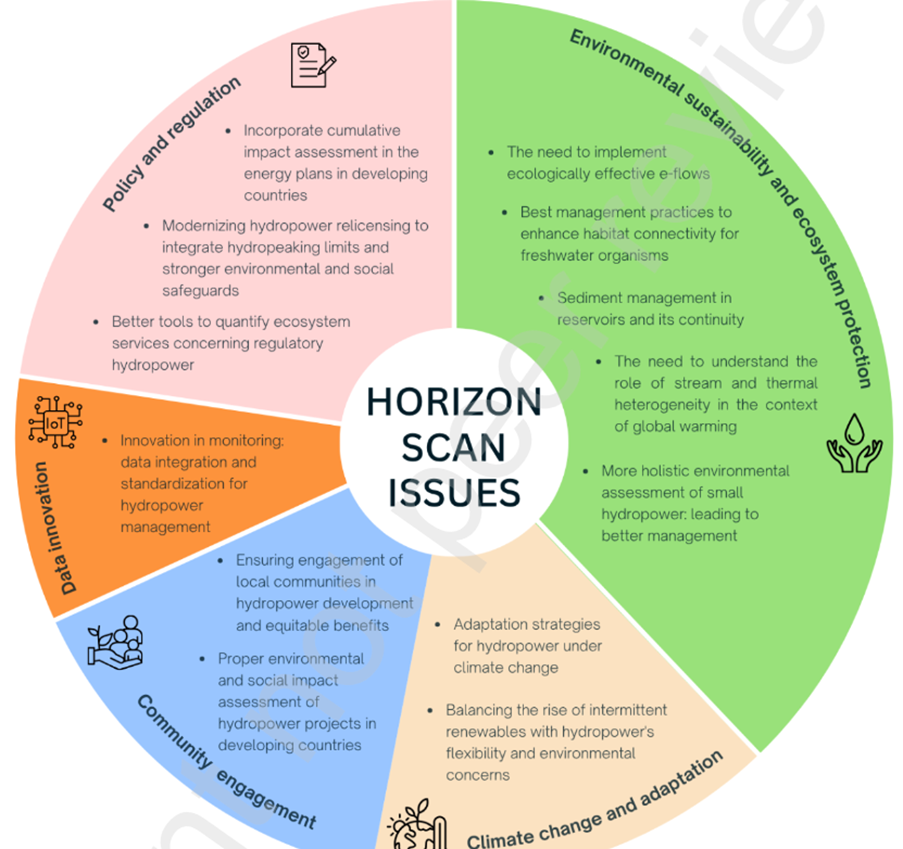

The paper presents over ten well-known, and largely intractable, problems common in hydropower development, framing them as “novel and important.” These are grouped into five “priority areas”: (i) environmental sustainability and ecosystem protection (5 issues), (ii) climate change and adaptation (2 issues), (iii) community engagement and social sustainability (2 issues), (iv) data innovation and monitoring (1 issue), and (v) policy and regulation (3 issues).

Figure source: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5377117

Most of the issues identified are related to systemic and long-standing shortcomings in the hydropower sector, such as the failure to manage environmental flows, rampant river fragmentation, unresolved sediment flow disruption, and the unfulfilled need for basin-wide cumulative impact assessments. These problems were extensively documented in the seminal reports of the World Commission on Dams (2000), a source conspicuously absent from the paper’s references. The concise problem statements suggest that in the intervening 25 years, these challenges have not only persisted but have exacerbated, with no viable solution pathway having been widely adopted by the industry or governments.

Addressing these topics, the paper correctly states that, “Sustaining or restoring longitudinal connectivity through careful site selection, sustainable technology, data-driven operations, and, where necessary, selective barrier removal is, therefore, essential to hydropower’s ability to deliver low-carbon electricity while meeting global freshwater biodiversity goals.” This is a commendable and progressive statement. However, the paper fails to provide a credible assessment of how the current industry or governments could be incentivized to follow this path, especially in the developing world.

The paper does introduce several genuinely innovative topics: the recognition of a need to sustain thermal refugia in streams, the application of AI and eDNA in hydropower management, and a call for holistic, basin-wide assessments for small hydropower projects. The authors rightly note that such projects are often extremely harmful to the environment while bringing minimal economic benefits.

Less convincing is the discussion on quantifying the ecosystem services of large hydropower. This appears to echo the industry’s controversial attempts to justify large reservoirs by misinterpreting the “ecosystem services” concept—for instance, by framing reservoir-provided recreational opportunities or regulated downstream flows as “ecosystem services“.

The paper effectively highlights the conflict between hydropower’s grid-balancing flexibility and its environmental costs. It points to the controversy of using hydropower to support the deployment of solar and wind, a practice that often results in severe “hydropeaking”—erratic flow changes detrimental to aquatic ecosystems. The paper cites a telling example from Norway, where “proposed limitations on peaking have been rejected to maintain system balance with wind energy.”

The “scan” also laments the “low deployment rates of pumped storage (especially closed loop PSH).” This claim is questionable, as sources like the Global Energy Monitor report that as of mid-2025, pumped storage projects constitute approximately 60% of the global hydropower pipeline.

The authors conclude: “Ultimately, the future of hydropower lies in its ability to adapt, balancing the grid-supporting flexibility needed for renewable integration with the protection of the aquatic ecosystems essential for long-term sustainability.” However, the underlying assumption that hydropower is the ideal tool for this “balancing act” is not sufficiently substantiated in the paper.

Under “Community Engagement and Social Sustainability,” the authors rightfully observe that community engagement is typically inadequate and that environmental and social assessments in the “Global South” are often treated as a mere “tick-the-box” exercise. They recommend Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) as a “first step” for involving affected communities. However, the paper omits the critical principle that FPIC is not just a first step, but a process that must respect a community’s right to say “no,” effectively making it the final word in the planning process.

Despite identifying many critical problems, the paper lacks clear conclusions about the feasibility of or credible pathways for resolving them. It stops short of addressing the fundamental question of whether “sustainable hydropower” is achievable at all. This is a significant omission, as the numerous, seemingly intractable problems detailed in the paper naturally lead to this very question.

The paper opens with the statement that “Hydropower is the backbone of renewable electricity generation worldwide,” a claim taken directly from the International Hydropower Association (IHA). It neglects to mention that by 2024, hydropower’s share of newly installed renewable capacity barely exceeds 2%, and its global production has stagnated for years, while solar and wind together now generate far more electricity. Furthermore, it is silent on the fact that over the last 15 years, the cost of hydropower-generated energy has increased substantially; in 2024, it is 30% more expensive than solar and 65% more than wind, with construction costs twice that of onshore wind and three times that of solar. In essence, the paper is built on the questionable premise that conventional hydropower is a crucial precondition for the “green transition.” The statistics, however, strongly suggest this assumption is outdated.

An analysis of the 37 co-authors reveals a potential source for this reluctance to draw firm conclusions. Based on their affiliations, a significant number are from hydraulic engineering firms, hydropower companies, and related consultancies, with the remainder from academia. The paper describes its method as a “democratic, structured, iterative process for collecting views and reaching consensus” among a “final group of 37 participants [representing] a balanced mix of academia, research, industry, and policy/regulatory bodies.” The composition, however, strongly suggests a group of industry insiders—consultants, engineers, and officials—who, while knowledgeable, are not positioned to question the fundamental legitimacy of continued hydropower development.

Notably absent from this “balanced mix” are experts from affected communities, indigenous groups, academics known for critical reviews of hydropower, conservation organizations, and environmental NGOs. It appears this group explicitly excluded any voices that might fundamentally question the future of the hydropower industry.

If this interpretation of the authorship is correct, then the paper is indeed a remarkable document. It represents a moment where hydropower proponents themselves acknowledge the immense, perhaps insurmountable, challenges and controversies facing their sector. For industry insiders, it is a bold and progressive work that reveals the deep conflict between continued hydropower development and the preservation of global biodiversity. Its publication could signal a revolutionary shift in the mainstream perception of hydropower from within its own expert community.

However, this praise cannot overlook the fundamental flaw in its methodology. This “horizon scanning” effort is inherently biased at its foundation, reflecting only one side of the debate on the future of conventional hydropower.

It is time to begin a genuine dialogue.

Eugene Simonov, Doctor of Conservation.

Rivers without Boundaries International Coalition