Source: Rivers.Help!

In the Tajikabad district of Tajikistan, a large mass of ice broke off from the glacier at the top of Ismoil Somoni peak. According to preliminary estimates, the size of the ice block is about two kilometers long, 25 meters high and up to 200 meters wide. The situation may worsen if, after heavy rains, new masses of ice begin to break off from the glacier. With a favorable combination of circumstances, the melted fragments of the glacier will simply flow into the Surkhob River 100 kilometers above the construction site of the Rogun Dam.

The incident that occurred on October 25 has so far been without casualties and destruction, but it has become another terrible reminder of the processes that are gaining momentum in the highlands of Asia. Experts attribute the incident to climate change, which accelerates the melting of glaciers and increases the danger of natural disasters. What has happened is an alarming symptom of a global trend that threatens the stability of entire regions. Scientists confirm that even the so-called Pamir-Karakorum anomaly – an area where glaciers remained relatively stable until recently – has come to an end. Now these “last bastions” have begun to rapidly lose ice mass.

The main danger is not the reduction of glaciers in itself, but its cascading consequences for downstream infrastructure. First of all, hydroelectric power plants – the basis of energy in many Central Asian countries – are under attack. Accelerated melting of glaciers leads to the formation and rapid growth of glacial lakes. Unstable moraine dams holding millions of cubic meters of water can be breached as a result of a landslide, heavy rains or ice collapse, causing destructive mudflows, known as breakthrough floods of glacial lakes. It is these phenomena that pose a direct threat to dams, bridges and settlements. A vivid and tragic example of this vulnerability is the experience of India, a rising superpower that, despite all its resources, turned out to be helpless when faced with the destructive power of glacial catastrophes.

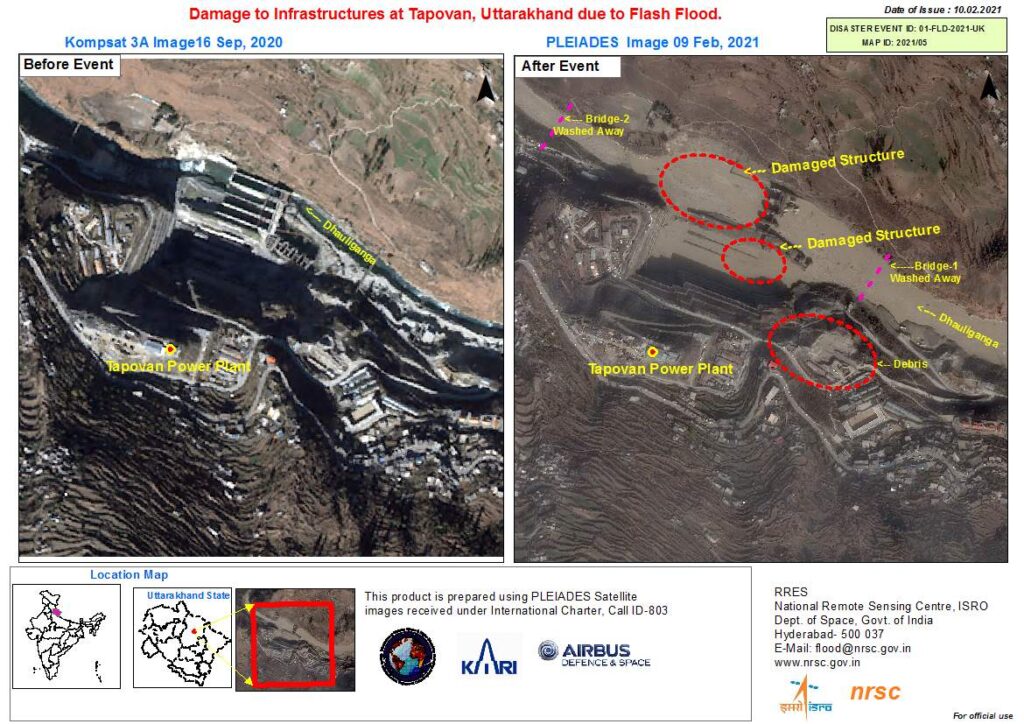

In October 2023, in the Indian state of Sikkim, the breakthrough of the South Lhonak glacial lake led to a cascading flood. The flow of water and debris in a matter of minutes demolished the 60-meter dam of the Chungthang Teesta III hydroelectric power station with a capacity of 1200 MW. The stream continued its destructive movement, damaging four more Dams downstream and causing widespread destruction up to the border with Bangladesh. This event was not a surprise to scientists: glaciologists warned several years before the disaster that South Lhonak Lake was a “time bomb” due to the rapid growth caused by the melting of the glacier. The tragedy in Sikkim was an ominous repetition of the disaster of 2021 in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, when the collapse of a glacier on Mount Ronti caused a flash flood that destroyed two Dams – Rishiganga and Tapovan Vishnugad – and claimed the lives of more than 200 people. It is noteworthy that even after a similar devastating flood in 2013, the Supreme Court of India instructed an expert commission to assess the risks, and it recommended stopping the construction of Dams in this “disaster-prone” region. However, these warnings were ignored.

The paradox is that many of these hydropower projects were built under the slogan of “clean” energy, designed to reduce CO2 emissions. The Rishiganga project has even been approved under the UN Clean Development Mechanism. However, as practice shows, the construction of such facilities in fragile high–altitude ecosystems is a dangerous and short-sighted enterprise. Since the most convenient and safe places for the construction of Dams have already been mastered, energy companies around the world are moving further and further upstream, to more risky areas. The problem is aggravated by the fact that the design of many dams is often based on outdated climatic data that overestimate the amount of precipitation and underestimate the potential damage from flooding and erosion. “Hydropower plants are often planned based on the climate of the past – a climate that is probably no longer relevant,” notes Omero Paltan, a climate researcher at the University of Oxford.

India’s experience poses uncomfortable questions for Tajikistan and other Central Asian countries, where hydropower is also a strategic industry. Will the dam builders in the region, faced with similar, if not greater, climate challenges, be able to counter the threats that one of the world’s largest economies cannot cope with? The instability of glaciers requires a revision of approaches to risk management and energy strategy. Faced with the growing vulnerability of hydropower, India is now developing solar energy even faster by diversifying energy sources. Which way will Central Asia go? The countries of the region face a difficult choice: to continue to rely on hydropower with its increasing risks or to invest in alternative, safer renewable energy sources. The break–off of a part of the Ismoil Somoni glacier in Tajikistan is a signal that the time for making strategic decisions is rapidly running out, and the price of inaction can be catastrophic.

Alexander Eskendirov (Rivers.Help!) https://rivershelp.org/n/1804