The Rogun HPP construction project in Tajikistan, in its current form, involves the forced resettlement of up to 60,000 local residents from the inundation zone. These people must leave their homes and their land to start a new life from scratch. Proponents of the project insist that this is the price of progress–tens of thousands of people must give up their land and homes so that the state can receive funds from exporting electricity from the HPP, and the Rogun Dam can become the tallest rock-fill dam in the world.

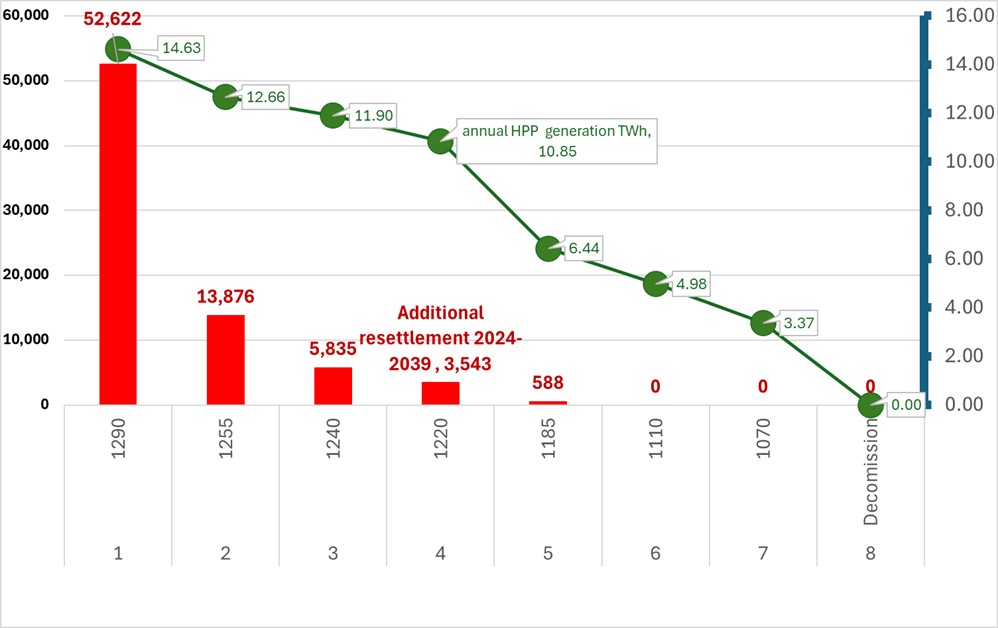

Yes, this is the price of progress. But only if progress is considered synonymous with maximizing the profits of Tajik and international construction companies, without considering any humanitarian aspects. The project developers opted for the option of building the tallest dam, justifying it with the economic benefits of electricity exports. In doing so, they dismissed an alternative option in which the Rogun reservoir level would have been just 35 meters lower, but would have avoided the forced resettlement of 32,000 people, which is more than 60% of the total number of resettled people. The loss in electricity generation would have been only 18%. However, this scenario was apparently not considered progressive enough by the project developers. Although their own progressiveness is also highly questionable: the very justification for choosing the maximum HPP dam-height option in the project documentation is based predominantly on outdated data from a decade ago and does not account for current economic realities or the development of alternative energy sources, such as solar and wind power plants, which could have fully compensated for that modest 18% generation shortfall.

The statistical data on which the resettlement plans for the Rogun HPP inundation zone are based appear unreliable and contradictory. In the project documentation, the total number of people subject to forced resettlement is constantly increasing: from 42,000 to “almost 60,000,” with no justification provided for these changes. The figures in the documents often contradict each other. For example, in one place, it states that labor migration is the main source of income for 54% of households, while in another, it says that only 3% of households include labor migrants. This confusion indicates a lack of an accurate count of all affected individuals, especially those working abroad (primarily in Russia). Without a clear understanding of how many people and with what needs require support, it is impossible to develop adequate assistance measures. Furthermore, the resettlement plans do not account for the natural division of large families into several new households after the move, which could lead to a serious underestimation of housing and resource needs.

The quality of the new resettlement sites is of particular concern. The documents acknowledge that in many new settlements, there are serious problems with access to water, arable land, and pastures. There is evidence that in some new settlements, drinking water is supplied for only 30 minutes a day. This directly contradicts international requirements, which state that living conditions in the new location must be at least equivalent to the previous ones. The results are already noticeable: according to the plan’s own data, after resettlement, the share of households engaged in irrigated agriculture fell from 44% to 6%, while the share of families without livestock rose from 19% to 56%. Instead of restoring their traditional agrarian way of life, people are effectively being pushed to abandon agriculture and join the ranks of labor migrants or unskilled workers, threatening the destruction of community ties and the creation of pockets of poverty.

The compensation methodology also raises serious concerns. Until July 2024, a deduction for depreciation was applied when assessing the value of property left behind in the inundation zone, which is a direct violation of the “full replacement cost” requirement. As a result, 778 already resettled families received undervalued compensation. Although this practice has been discontinued (in 2024), people are being told to apply to a specially created bureaucratic body–the Grievance Redress Mechanism–to rectify the situation. This approach essentially shifts the responsibility onto the victims themselves. Moreover, statistics directly confirm the low effectiveness of this body: while 25–50% of households report a shortage of funds, only 3% have been able to receive additional assistance through the Grievance Redress Mechanism.

Could it be that the project simply lacks the money for resettling local residents from the inundation zone? After all, building the world’s tallest dam is an extremely expensive undertaking. Unfortunately, we cannot verify this. The Rogun HPP project budget allocated for resettlement is non-transparent but appears to be truly insufficient. The total budget listed in the “second phase” resettlement plan is $87.5 million for 17,000 individuals to be resettled, but a breakdown of expenses is missing. For example, $44 million is allocated for “infrastructure restoration,” but with no itemization for schools, hospitals, or roads. The budget for direct compensation for expropriated homes and property is significantly more modest and, based on the scant data provided, amounted to less than $1,000 per resettled person. The “livelihood restoration plan” has no separate budget of its own at all, relying on other foreign aid programs, which does not guarantee stable and sufficient funding. Meanwhile, the total cost of resettlement from the Rogun HPP inundation zone varies in different project documents from $278 million to $380 million–a difference of $100 million that is never explained. This financial uncertainty undoubtedly jeopardizes the fulfillment of obligations to the resettled people.

Finally, the proposed resettlement timeline looks completely unrealistic. During the “second phase” (2017–2026), only about 7,800 people have been resettled over seven years. According to the new plan, published in August 2024, another 9,000 people are planned to be removed from the Rogun HPP inundation zone by the end of 2026, meaning in less than a year and a half. Such a sharp acceleration will inevitably lead to a decline in the quality of site selection and preparation, and to insufficient information and consultation, which could result in the forced eviction (removal) of local residents as the Rogun reservoir fills.

Our public environmental organization and our colleagues in the international Rogun Alert coalition are convinced that the resettlement plans for the Rogun HPP, in their current form, do not bring improvements but rather risk worsening the lives of thousands of people. To prevent the project from becoming a symbol of human tragedy, a fundamental review of these plans is necessary. This requires a transparent and honest analysis of project design alternatives aimed at selecting the option with minimal resettlement, an accurate count of all affected individuals, ensuring new residential sites are equipped with all necessary resources before the move, fair compensation, and realistic timelines.

We remain convinced that even today, progress is measured not by the height of dams built or the volume of kilowatt-hours generated, but by the maximum preservation of the environment and human fates.

Alexander Kolotov,

Director of the “Rivers without Boundaries” Public Foundation.

Original in Russian published by Nezavisimaya Gazeta

The source of title image Rivers.Help!